In the previous 0.7 version, I optimized the overall performance of Nature, including TCP/UDP/HTTP, CPU, String, GC, and Closure. After the release, I conducted a performance comparison test with other programming languages to give developers a clearer understanding of Nature's performance.

The relevant test code is available in the https://github.com/nature-lang/benchmark repository. This is the first performance test, so previous versions of Nature were not used for comparison. Because Nature and Go use the same architectural design, the latest version of Go was used as the benchmark for testing, and Rust and Node.js were introduced for reference in appropriate areas to avoid being misled by machine performance limitations.

| Configuration Item | Details |

|---|---|

| Host Machine | Apple Mac mini M4, 16GB RAM |

| Test Environment | Linux VM Ubuntu 6.17.8 aarch64 8GB RAM |

| Compiler / Runtime Version | Nature: v0.7.2 Golang: 1.25.5 Rust: 1.92.0 Node.js: v25.2.0 |

IO

Write a simple HTTP Server using the language standard library

Nature Code Example

import http.{server, request_t as req_t, response_t as resp_t}

fn main() {

var app = server()

app.get(‘/’, fn(req_t req, ptr<resp_t> res):void! {

res.send(‘hello nature’)

})

app.listen(8888)

}Test Command ab -n 100000 -c 1000 http://127.0.0.1:8888/

Test Results

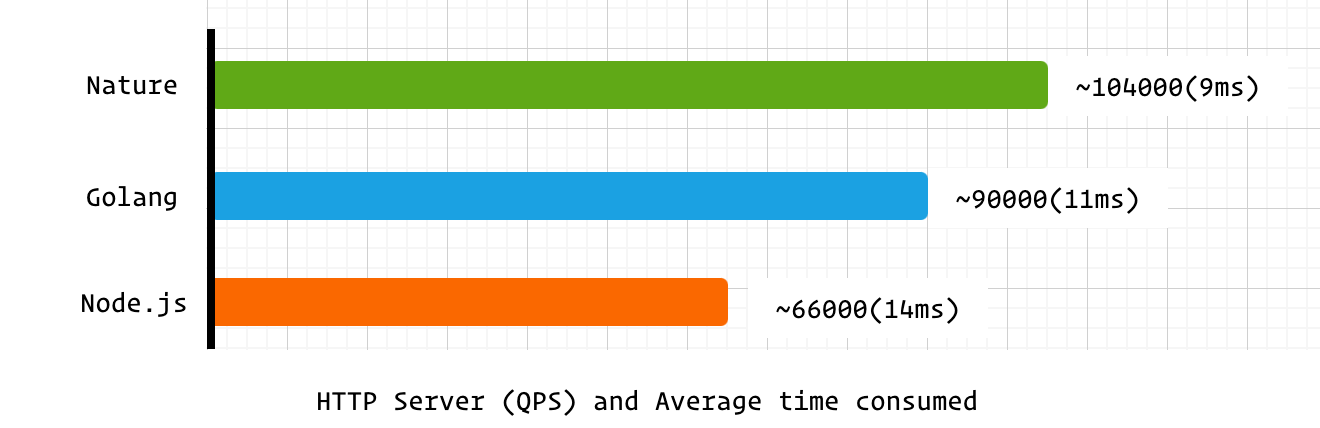

HTTP Server This is a comprehensive performance test of the programming language, involving memory allocators, garbage collection (GC), data structures, coroutine schedulers, and I/O loop processing.

Nature's performance in this aspect is very good, and it is also ahead of Go. In terms of technical architecture, Nature uses libuv as its I/O backend, consistent with Node.js. However, as an AOT (Ahead-of-Time) programming language, Nature has a natural advantage in overall performance compared to JIT (Just-In-Time) programming languages.

If you want to quickly experience developing APIs using Nature, you can refer to the project https://github.com/weiwenhao/emoji-api.

CPU

Calculate 1 billion PIs using the Leibniz formula

Nature Code Example

import syscall

import fs

import strings

import fmt

fn main() {

var f = fs.open(‘./rounds.txt’, syscall.O_RDONLY, 0).content()

var rounds = f.trim([‘ ’, ‘\n’]).to_int()

var x = 1.0

var pi = 1.0

int stop = rounds + 2

for int i = 2; i <= stop; i+=1 {

x = -x

pi += x / (2 * i - 1) as f64

}

pi *= 4.0

fmt.printf(‘%.16f’, pi)

}Test Command hyperfine --warmup 3 ./pi_n ./pi_go ./pi_rs “node main.js”

Test Results

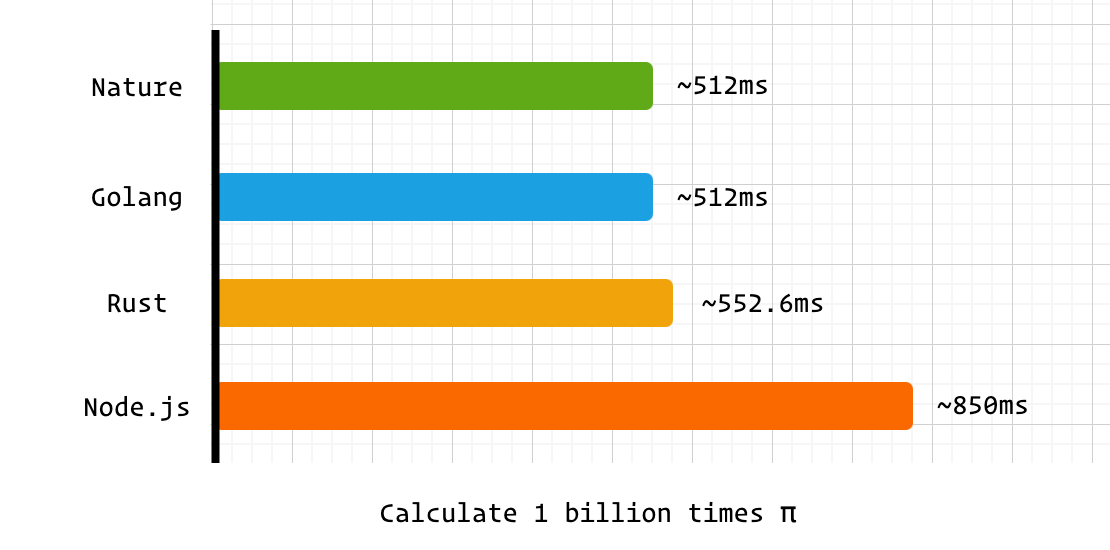

This is a simple CPU computation test, which, in my opinion, mainly tests the utilization of register allocation in programming languages. Rust uses a Greedy graph coloring variant register allocation algorithm, while Nature/go/nodejs all use a linear scan register allocation algorithm. Since there are no function calls in the loop and no register overflow is involved, Nature and Go perform very well in this regard.

Recursion

The fib(45) function is computed using the classic recursive Fibonacci sequence to test the high-frequency function call overhead of the language.

Test command hyperfine --warmup 3 --runs 5 ./fib_n ./fib_go ./fib_rs “node fib.js”

Test results

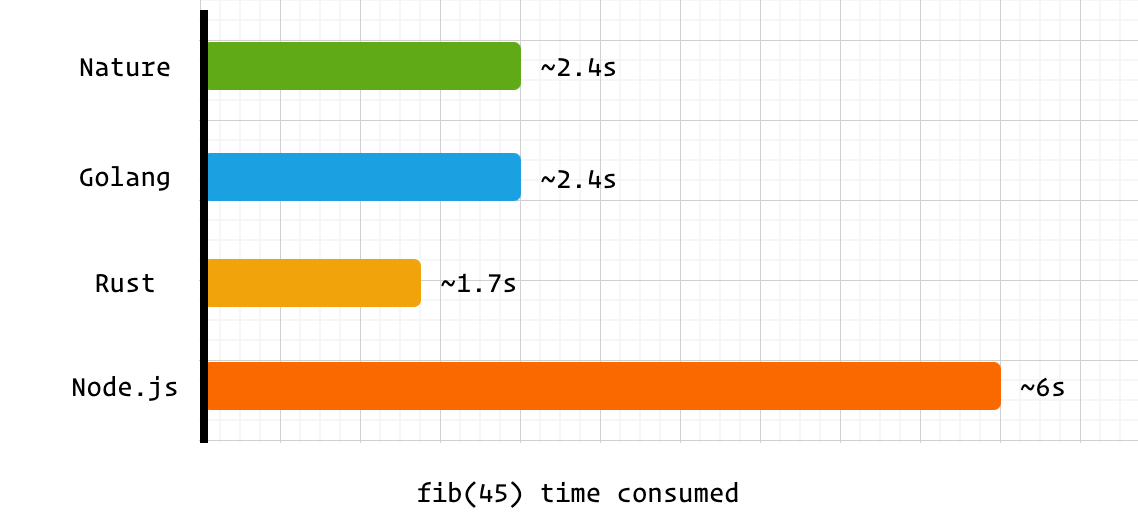

Nature and Go use their own custom compiler backends, resulting in similar performance. One reason for Nature and Go higher execution time compared to Rust is the need for preprocessing before function execution. For example, Go needs to handle stack resizing.

// more stack

f9400b90 ldr x16, [x28, #16]

eb3063ff cmp sp, x16

540002a9 b.ls 7869c <main.Fib+0x5c> // b.plas

Whereas Nature handles GC safepoints

400284: d0003490 adrp x16, a92000 // global safepoint

400288: f9474210 ldr x16, [x16, #3712]

40028c: b5000250 cbnz x16, 4002d4 <main.preempt>

Go uses signal-based preemptive scheduling, so it doesn't need to insert Safepoints during instruction execution, which further improves the speed of instruction execution and function calls. However, since Go uses independent-stack coroutines, it has to consider whether there is enough stack space during function calls.

Nature did not choose signal-based preemptive scheduling. Instead, it uses cooperative scheduling as the main approach plus Safepoint instruction preemption. This may cause GC pauses in some extreme scenarios, but it also offers greater flexibility and controllability.

As for why preemption or Safepoints are needed, this relates to the classic GC STW (Stop-the-World) problem. Modern programming languages' GC typically uses concurrent mode, which requires pausing all threads at a critical moment before safely enabling write barriers. Even though this STW phase is very short, it remains a point of criticism among developers.

When it comes to coroutine stack design, it's another interesting choice problem. Stackless coroutines offer extreme performance but suffer from async pollution. Independent-stack coroutines avoid async pollution but have disadvantages in performance and memory usage. Shared-stack coroutines, on the other hand, are a middle ground between the two, providing better performance and memory usage while also avoiding async pollution.

C FFI

By calling the sqrt function from the C standard library 100 million times, we tested the efficiency of collaboration with the C language.

Nature Code Example

import libc

fn main() {

for int i = 0; i < 100000000; i+=1 {

var r = libc.sqrt(4)

}

}Test Command hyperfine --warmup 3 --runs 5 ./ffi_n ./ffi_go

Test Results

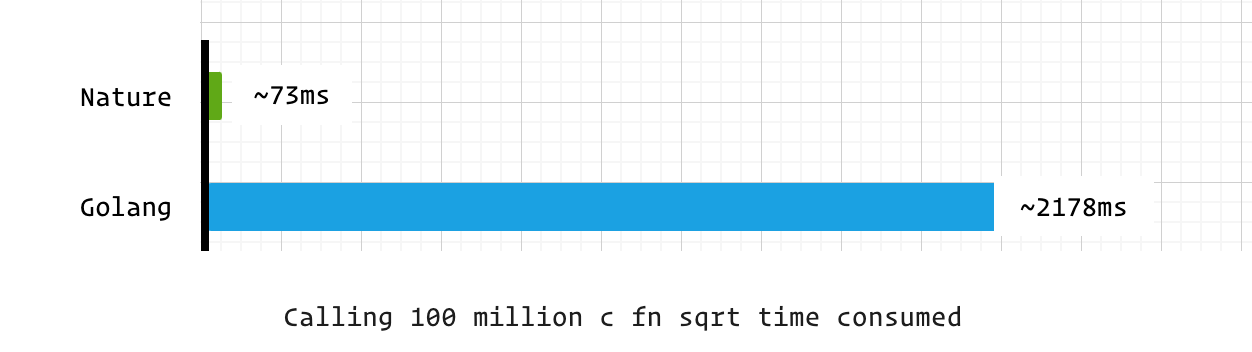

The performance gap is striking. Go's independent stack and signal-based preemption design leads to compatibility issues with C and other libraries that conform to the ABI specification.

Nature, on the other hand, implements a complete ABI specification and type mapping, and its shared stack coroutine design allows Nature to call ABI-compliant codebases without loss of performance.

In high-performance computing and low-level hardware operations, Nature can seamlessly integrate core modules written in C/assembly, compensating for the shortcomings of GC languages in extreme performance scenarios, balancing development efficiency and low-level performance.

Coroutines

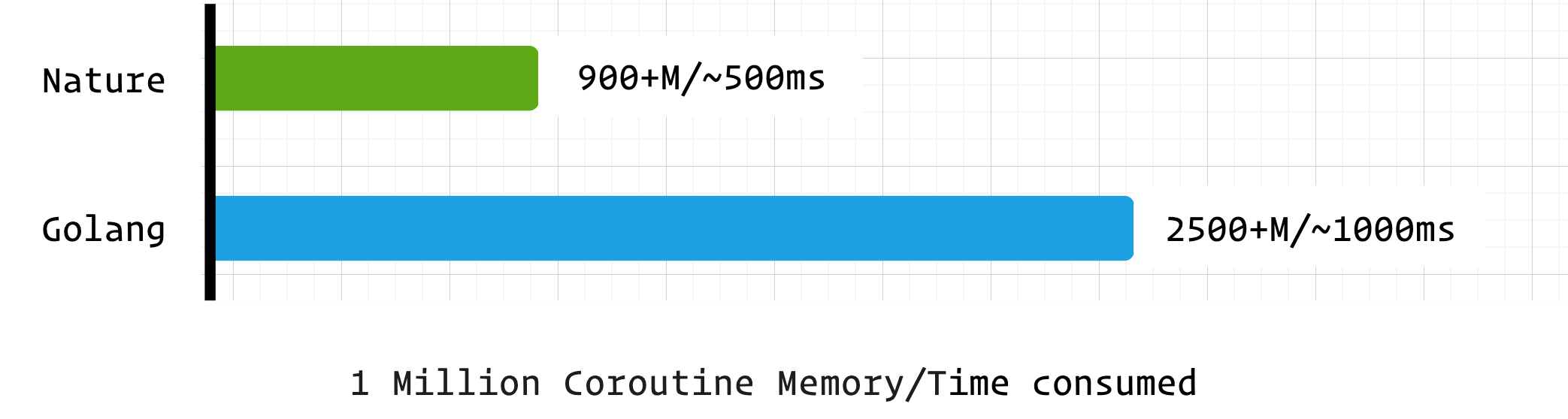

Nature inherits the excellent design principles of Go, including coroutines. Through a scenario involving the creation, switching, and simple computation of millions of coroutines, we evaluate the coroutine scheduling efficiency, memory usage, and response speed of Nature and Go.

Nature Code Example

import time

import co

var count = 0

fn sum_co() {

count += 1

co.sleep(10000)

}

fn main() {

var start = time.now().ms_timestamp()

for int i = 0; i < 1000000; i+=1 {

go sum_co()

}

println(time.now().ms_timestamp() - start) // create time

int prev_count = 0

for prev_count != count {

println(time.now().ms_timestamp() - start, count)

prev_count = count

co.sleep(10)

}

println(time.now().ms_timestamp() - 10 - start) // calculate time

} Test Results

Thanks to its shared-stack coroutine technology, Nature demonstrates exceptional overall coroutine performance, with memory consumption significantly lower than Go. Given Nature's strong showing in coroutine benchmarks, this release actually contains no coroutine optimizations. Nature's coroutines still hold substantial optimization potential in areas like memory usage and struct design.

Summary

Through the syntax examples and benchmark charts above, you have gained a clearer understanding of the Nature programming language. In the benchmark tests, Nature has already delivered excellent performance, and as an early-stage programming language, its runtime and compiler still have significant room for optimization.

Even if you don't plan to use Nature, it is still an emerging programming language worth paying attention to, especially in areas such as cloud native, network services, API development, agent development, command-line tools, and infrastructure construction.

As a general-purpose programming language, we aim for Nature to be applicable in more scenarios. Key features to be implemented in the future include:

-

Convert to the readable Go programming language to take advantage of the Go language ecology. This is a helpless thing, but it must be done for the usability of Nature;

-

GUI library adaptation: While preserving the existing event loop mechanism, we will enable Nature to better integrate with C/C++ GUI libraries while ensuring GC correctness, providing usable GUI development libraries.

-

WASM 3.0 adaptation: WASM 3.0 now supports GC, allowing Nature to translate AST directly to the WASM backend without relying on complex runtime environments.

-

Controllable memory allocator and unsafe bare function support: This forms the foundation for GUI/WASM 3.0 adaptation. If designed properly, Nature will truly become a systems programming language suitable for high-performance system development.

-

AI adaptation: Integrating AI as a code assistant for Nature to enable writing correct and elegant Nature code, including optimizing error prompts, improving testing capabilities, and building searchable standard library documentation.

-

AI coding verifiability exploration: This is a critical goal for Nature and represents a distinct effort from the AI adaptation mentioned above. Once this feature is complete, Nature will become one of the most suitable programming languages for LLM-generated code.

Nature is a community-driven and open and free programming language that can accept advanced and even radical technology iteration methods; and supports AI-assisted programming to contribute code (use cladue opus4.5+ or equivalent model and do code review and testing).

If you're interested in or have ideas for any of the above jobs, feel free to submit a github issue or communicate with me via email at wwhacker@qq.com. 🍻